After making the case for Dave Concepción for the Hall of Fame, I have to admit something: I felt a little guilty. Davey certainly deserves to be enshrined in Cooperstown, but I ignored the single player in Reds history who deserves induction even more.

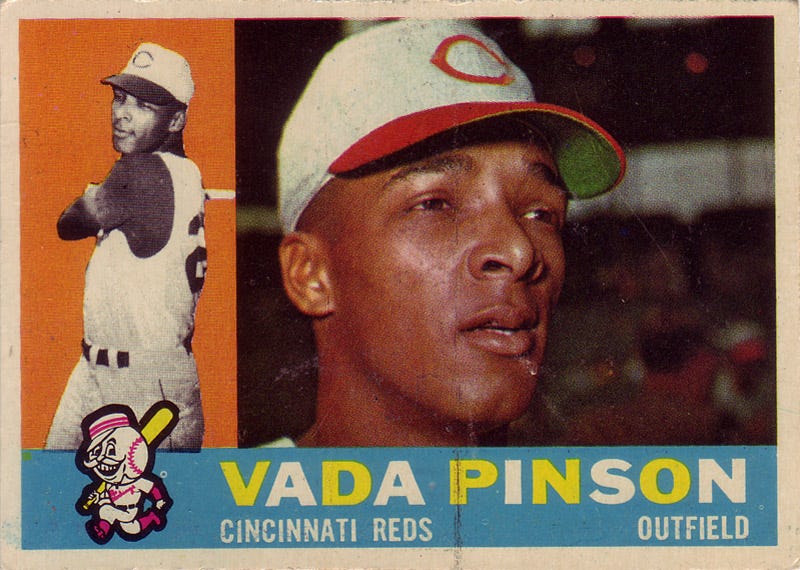

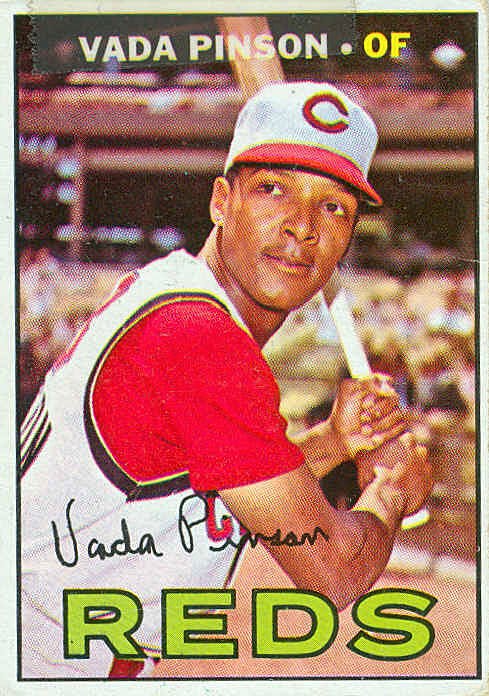

Some ballplayers have a moment that defines them with a thunderclap — think Willie Mays spinning under that famous World Series fly ball, or Hank Aaron launching his record-breaking home run that thundered around the sporting world. Others, of course, announce themselves by simply running out to center field one day and never really leaving the consciousness of anyone who saw them play. Vada Pinson was one of the latter: a smooth, graceful, softly brilliant presence who glided through the 1960s with a skillset that should’ve cemented him in Cooperstown long ago.

For some Reds fans — especially those who remember Pinson taking the field at Crosley — his exclusion from the Hall of Fame is one of baseball’s quiet mysteries. Quiet, perhaps, because Pinson himself was never loud, never brash, never comfortable boasting about his own accomplishments. And yet, the numbers, the feats, the remarkable longevity? They all fairly scream: This man belongs in Cooperstown.

Pinson was still a teenager when he first suited up for the Reds in 1958. He struggled a little — sure, most kids do at 19 — but once he returned to the big leagues in September, he never wore a minor league uniform again. He didn’t need to. Cincinnati fans watched the scrawny, lightning-fast kid turn on the jets in center field, and they understood they had something special on their hands.

They were right. Over his first seven full seasons, from 1959 to 1965, Pinson battered National League pitching. The raw highlights:

A .310 average.

A near-annual ticket to the league leaderboard in hits, doubles, and runs.

A 20 HR / 20 SB threat in five separate seasons (back when that really meant something).

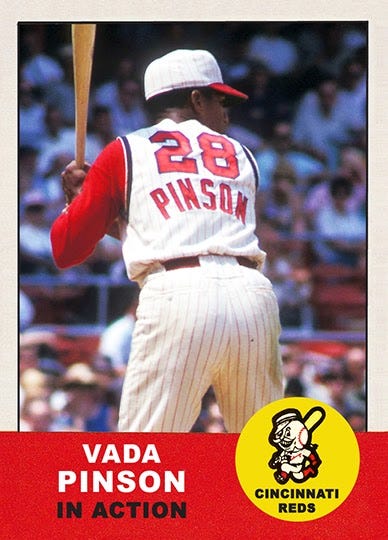

Some of the best center-field defense in an era dominated by Willie Mays and Roberto Clemente.

Let’s not neglect the context. In those days, if you played center field in the National League, you bumped elbows with Mays, Clemente, Henry Aaron (when he moved around the outfield), Curt Flood, and more. For Vada Pinson to stand out in that crowd would have been like an actor upstaging Brando in the ‘50s — it’s just not supposed to happen. But Pinson often came close, piling up hits and extra-base prowess at a rate that made him a star.

If you’ve heard of Pinson at all, you may have heard this stat: He’s one of only nine players in baseball history to collect at least 2,700 hits, 250 homers, and 300 steals. The other eight? Names like Willie Mays, Barry Bonds, Alex Rodríguez —pretty decent company, right? Pinson finished his career with 2,757 hits, 256 homers, 305 stolen bases. If you combine speed and power and defensive prowess, only a handful of center fielders in history have done what he did.

And yet, Pinson was overshadowed. Frank Robinson, his teammate (and close friend from their Oakland youth days), was an MVP by age 25; Pinson never had that single crowning achievement. His best MVP showing was third place in 1961 (when the Reds won the pennant). He earned two All-Star nods early on (four, actually, but they were in the years that MLB played two All-Star Games every season), but — somehow, unbelievably — never returned despite authoring better seasons in later years.

Such is the story of Pinson’s life in baseball: overshadowed by a Hall of Fame legend in his own outfield, overshadowed by big personalities on bigger stages, overshadowed by an era that tended to focus on the biggest sluggers.

Here I’ll make a similar argument that I made when considering Concepción’s Hall of Fame case.

Harold Baines’s induction will almost certainly continue to be a lightning rod for many baseball fans and scribes. Baines was an excellent hitter, yes, but few would claim he carried a team or defined his position. His supporters, presuming there are some, can point to longevity and consistency. His detractors say: “He didn’t lead the league in anything, he didn’t win big awards, he never reached a milestone like 3,000 hits.”

So, what do we say when we examine Vada Pinson in that same light?

Longevity: Pinson played 18 seasons, accumulating more than 2,700 hits (Baines reached 2,866 hits but in four additional seasons, mostly as a designated hitter).

Peak Value: Pinson led the league in categories 11 times (hits, doubles, triples, runs). Baines led the league a grand total of once (slugging percentage in 1984).

All-Around Play: Pinson patrolled center field with grace and speed, amassing more than 170 outfield assists and winning a Gold Glove in 1961. Baines primarily served as a DH, accumulating fewer than 40 career WAR by some measures, while Pinson accumulated 54.2.

As I’ve said, if Baines’s induction opened the gates to reexamining borderline candidates with strong counting numbers and consistent production, Pinson, by any fair metric, leaps to the top of that “reexamination” list. Over the years, the Hall has historically failed to give certain players their due, especially if they aged poorly or lacked a charismatic storyline (or were alleged to have used PEDs, I suppose). Pinson wasn’t hitting .300 at age 39, true enough. But what he did through his 20s, how he soared into his early 30s, was the stuff of Cooperstown. Like Concepción, I’ve changed my mind on Pinson. He absolutely deserves enshrinement.

So why hasn’t Pinson been elected to this point? If we’re going to argue in his favor, we have to acknowledge the reasons he hasn’t been enshrined yet.

Rapid Decline Post-Cincinnati

After being traded to St. Louis following the 1968 season, Pinson’s production tailed off sharply, with a .265/.301/.390 line over his final seven seasons. That fade — while common among speedy outfielders once they lose that first step — may have stuck in voters’ minds.Overshadowed in a Stacked Era

This is a big one, in my opinion. Pinson played in an outfield fraternity that included Mays, Aaron, Robinson, and Clemente. Even players like Duke Snider and Richie Ashburn still lingered on the scene. Some Hall voters may have simply thought, “Well, he wasn’t Mays or Clemente.” No one was! That is an impossibly high bar.Personality and Public Perception

Pinson was famously quiet, conflict-averse, and overshadowed by the bigger stories in his clubhouse. He did, however, have an incident with a local beat writer, Earl Lawson, that led to a court hearing — an unfortunate footnote that didn’t help his relationship with the press. The flamboyant types get more headlines; the quiet ones too often fade from memory.The Fate of the 1960s Reds

Pinson was traded away just before the Big Red Machine took off, robbed of the team success that might have burnished his legacy. He also arrived in St. Louis right after the Cardinals’ run of World Series appearances ended, missing that championship glow in back-to-back stops. Unlucky!

But while rationalizing his absence from the Hall might be easy from a “he just wasn’t flashy enough” standpoint, it’s time we correct that narrative. The advanced metrics — WAR, OPS+, total bases—are kinder to Pinson than they are to many enshrined players. His 54.2 WAR surpasses the marks of Hall of Famers Tony Pérez (54.0), Lou Brock (45.4), Kirby Puckett (51.2), and more. Yes, WAR isn’t the sole determinant of greatness (nor should it be), but more and more these days, it’s the shorthand that baseball writers defer to.

Anecdotally, baseball lifers revered Pinson. Sparky Anderson hired him as a trusted coach. Frank Robinson considered him a confidant. Revisit old clips and you’ll see him exploding out of the box, pushing even a simple bunt into a heart-thumping, close play at first. You’ll see him roving center field in Cincinnati with an effortlessness that always seemed to belie the tension of the moment.

And the fans who saw him still recall that sense of awe. Talk to a longtime Reds supporter and you’ll hear them say, “He was so quick, so smooth — like Mantle without the fanfare.” It’s high praise, but not undeserved.

Character sometimes only comes into Hall of Fame discussions when it’s a negative: a scandal, a gambling issue, PED suspicion, or a legendary feud with the media. But baseball’s definition of “character” can extend the other way, too. By most accounts, Vada Pinson was a gentleman, a good teammate, an underrated mentor who left a positive impact everywhere he went — from the high schools of Oakland to the World Series with the Reds in ’61 to coaching gigs in Seattle, Detroit, and Florida.

We aren’t about to throw away the standards of Cooperstown, but if we’re opening our eyes to overlooked players — especially now that the committees have shown a willingness to induct guys like Baines — why not revisit Pinson, whose achievements, at their best, tower over Baines’s? Why not credit the grace and steadiness that made him the ideal outfield anchor for the Reds of the 1960s? Why not focus on the fact that in the pantheon of center fielders, he stands toe-to-toe with many of the game’s legends?

None of this is to say Vada Pinson was Willie Mays or Mickey Mantle. But he was certainly more than the quiet guy overshadowed by Frank Robinson. He belongs in that special conversation of players who combined speed, power, defense, and a consistent knack for greatness. If the Hall of Fame is designed to tell the full story of baseball, to honor those who shaped the game in meaningful ways, then Pinson’s story is a chapter worth telling.

I love reading about the 1961 Reds, perhaps the most under-remembered team in Cincinnati Reds history. That season, when the Reds finally found their way back to the World Series, Pinson was the spark. He led the National League in hits (208), slugged .504, and finished third in the MVP voting behind — who else? — his friend Frank Robinson and Orlando Cepeda. He roamed center field and turned in highlight after highlight, winning a Gold Glove as a cherry on top. No, the Reds didn’t beat the Yankees in the Series that year, but Reds fans of a certain vintage will tell you: the memory of Pinson sprinting out those extra-base hits, swiping bases, and rising to that moment remains one of Cincinnati baseball’s eternal postcards.

Let’s hope the Veterans Committee or Contemporary Era voters one day reconsider. Vada Pinson deserved a better fate in Hall of Fame voting. His shy, behind-the-scenes persona shouldn’t obscure the fact that, at his peak, he produced historic seasons and contributed meaningfully to his teams for nearly two decades. For many, that’s all the argument you need.

Cooperstown has room for a player who stood among the best center fielders of his generation, a player with nearly 2,800 hits, a man known for speed, grace, and a million quiet acts of baseball brilliance. It’s time we open those gates a little wider and let Vada Pinson in.

Thank you for keeping my father's memory alive. It means a great deal to me and truly honors his legacy.

My favorite player as a kid. Amazing seasons to start his career. His ages 20 & 22 seasons are probably amongst the greatest for those ages. Thanks, Chad, for presenting a great case!