Some time ago, I began a little project to name the 101 best Cincinnati Reds players of all time. The Big 101, if you will. Click here to see the full countdown so far.

In some ways, Lee May never really left Cincinnati. He wore the Reds uniform for only a handful of seasons — four full ones, really — but the mark he made, well, it remained. The more seasoned persons among you remember him well. May isn’t memorialized as flamboyantly as some of the more famous names from Cincinnati’s fabled Big Red Machine. You know all about Bench, Perez, Rose, Morgan. But if you were around long enough, you would recall that before the Machine truly revved up to a full roar, Lee May was cranking the ignition with his home run swing.

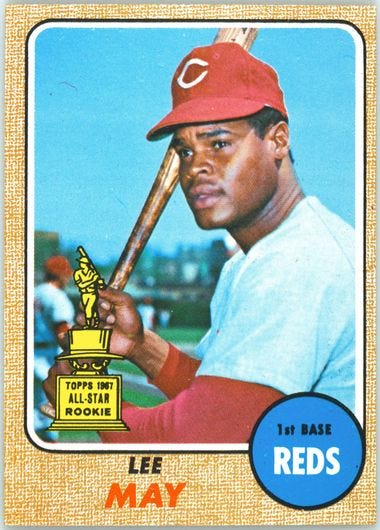

He was “The Big Bopper from Birmingham,” a moniker bestowed on him by teammate Tommy Helms. A good nickname, you’d say, for a man who stood six-foot-three and looked every bit the part of a legendary slugger. But though he looked the part, May was a kind of quiet thunder in the Reds lineup. People maybe didn’t see him coming. They’d hear the bigger, more famous names — Johnny Bench, Tony Perez, Pete Rose. Then they’d check the box score in the next day’s paper and notice that May, unheralded, had just launched one into orbit. Again.

May was born on March 23, 1943, in Birmingham, Alabama, a city saturated with baseball history and heavy with a complicated past. His family separated when Lee was young, but he flourished as an athlete — basketball, football, and most especially baseball. In high school, he was so big — so strong — that people questioned his birth certificate. He was just as good on a football field (the University of Nebraska had him on speed dial) as he was in a batter’s box. But a Reds scout by the name of Jimmy Bragan came calling, offering May $12,000 to sign, and that was that. May was on his way to the Reds organization.

Those early minor-league days exposed him not just to the wide world of baseball, but also to something deeper about America. In several stops — Tampa, Rocky Mount, Macon — he endured racist taunts and ugliness from the stands. If it embittered him, he never let it show when he finally made the big leagues. Maybe that’s why May carried himself with a certain grace; he’d seen both baseball’s joys and its harsh realities.

May played just a few late-season games in 1965 and 1966, but by 1967 he was a full-time major leaguer. He only hit 12 home runs that year, but they were 12 thunderclaps, enough to earn him The Sporting News Rookie of the Year award, if not the official BBWAA trophy. The next season he belted 22 home runs and knocked in 80, helping the Reds inch in the direction of something special.

If you close your eyes and imagine Crosley Field and its intimate walls, or the very first days of brand-new Riverfront Stadium, you can see May standing in the on-deck circle, bat wagging behind him, blinking with that stoic confidence. He’d stride to the plate, and the pitch would come in, and more times than not, he’d belt it. After his first full season, he hit 20 or more home runs for eleven consecutive seasons, and he drove in runs by the dozens. The Reds hadn’t won a World Series in three decades, but May made fans believe that just maybe, if everything went right, Cincinnati was finally on the cusp of another championship.

By 1969, that cusp felt very real. The Reds finished just four games out of first place in the newly formed National League West. The next season, under new skipper Sparky Anderson, the club roared to 70 wins in its first 100 games. People started calling them the Big Red Machine, and Lee May was right in the thick of the lineup, blasting 34 homers. The Reds won the pennant — their first since 1961 — and faced off against the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series.

Though the Reds fell in five games, May was magnificent. He batted .389 and recorded eight RBIs in just five games — tying a then-record. He delivered the only Reds victory of that Series with an epic three-run homer in the eighth inning of Game 4, a towering drive that seemed to whisk the ball right out of Memorial Stadium. For a few moments, you could almost feel the baseball world shift on its axis. And there was May, stoic and solid, rounding the bases, carrying Cincinnati’s championship dreams on his broad shoulders.

But the next season, 1971, changed everything — for Lee May and for the Cincinnati Reds. The club slumped to 79–83, despite May hitting a career-high 39 home runs and posting career bests in WAR (5.5) and OPS+ (147). Then, like a thunderbolt of heartbreak for Reds fans, on November 29 came the trade that would reshape baseball. General Manager Bob Howsam, on a quest to add speed and defense to Cincinnati’s lineup, sent May, Helms, and Jimmy Stewart to the Houston Astros for Joe Morgan, Jack Billingham, César Gerónimo, Ed Armbrister, and Denis Menke.

As if with the snap of a finger, May was gone. There was an uproar. The local press wrote with wide-eyed shock. May was the team’s MVP that year. Fans loved his big-swing heroics. He’d led the Reds with his power. Suddenly, he was out the door. How could the Reds deal him away?

“If the United States had traded Dwight Eisenhower to the Germans during World War II, it wouldn’t have been much different than sending (Lee) May and (Tommy) Helms to Houston,” wrote Enquirer sports reporter Bob Hertzel that day.

In hindsight, you can view that moment two ways. Yes, the Reds ended up winning three more pennants and two World Series in the years that followed — the definitive Big Red Machine. Bob Howsam’s bold trade turned them into a dynasty, anchored by the brilliance of Morgan, Bench, Perez, Rose, and so many others. But for Lee May, it meant that the history books would push him down a rung. His name would be overshadowed by the men he left behind.

But if you ask longtime Reds fans who followed the team in those transitional years—1967 to 1971 — they will tell you about Lee May. They’ll remember the last home run in the history of Crosley Field, the one May launched off Juan Marichal in 1970. They’ll remember that thunderous, wrist-flick swing and the basepath grin he occasionally flashed on the way back to the dugout. They’ll remember the Big Bopper giving a city hope.

Yes, he went on to great success in other uniforms: The Astrodome in Houston, where he kept right on hitting 20-some homers every year, then Baltimore, where he joined Earl Weaver’s team and led the American League in RBIs in 1976. He even made it back to another World Series with the Orioles in 1979. But in Cincinnati, no matter how many coaches would later wax poetic about “the same pitch that fooled him one at-bat he’d hit out of the park the next,” no matter how many times manager Sparky Anderson lamented losing him, May remains a cherished pillar. He is part of the bedrock that allowed the Big Red Machine to get rolling.

Sure, he’s not as famous as Rose or Bench or Perez—how could he be? He missed those glorious 1975 and ’76 seasons. You imagine him, in some alternate universe, still anchoring that infield at first base, celebrating a parade in downtown Cincinnati after the Reds conquered the baseball world. But in the real timeline, we’re left with the sweet sadness of wonder: Could it have been even more special if Lee May had stayed?

Maybe, maybe not. Probably not, I concede. In retrospect, I think we’re all glad that Joe Morgan arrived in Cincinnati, and that Bob Howsam had the guts to pull the trigger on that trade. But you have to feel a little bad for May, missing out on all the fun.

That feeling underscores why Lee May is often viewed as an underrated star. He finished his career with 354 home runs, 1,244 RBIs, and 2,031 hits. He is one of only eleven players in major league history to collect 100-RBI seasons for three different teams. He played 18 seasons, made three All-Star teams, and was inducted into the Reds Hall of Fame in 2006. But mention his name at Great American Ball Park these days and you’re likely to get a quizzical look in return.

But those who were around in that exhilarating stretch between 1967 and 1971 will say he was more than good; he was essential. It’s no exaggeration to suggest that without Lee May and his long, arching home runs, the Reds might have never been labeled the Big Red Machine in the first place. He was the battery that started the engine.

Lee May. The Big Bopper from Birmingham. The man who quietly — and quite literally — helped build the Big Red Machine. It might read like a footnote in baseball history, but in Cincinnati hearts, it’s a chapter all its own.

And it’s chapter number 48 in this countdown.